Through the Lens of Seydou Keïta’s Bamako Portraits

Acknowledged by many as ‘the father of African photography’, Foam Fotografiemuseum’s new exhibition of Seydou Keïta’s (b. 1921, Bamako – d. 2001, Paris) work shines a light on the wonderful beauty and fashion in mid-20th Century Africa, as well as the transformative time in Malian cultural and political history. As part of the last generation to be born under colonial rule, Keïta’s iconic portraits present an era that was in the process of being thrust into modernity, full of promise, strength and pride, with a slight hint of rebellion.

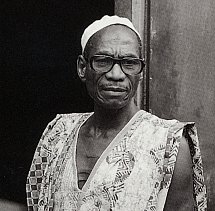

Seydou Keïta’s work is powerful and rare because it illustrates a time in African history from the voice of a black spectator, as opposed to the dominant white narrative that is so pervasive. Several great African empires passed through Mali’s history, Ghana, Maliké and Songhai, each controlling the trade across the Sahara and connecting it to civilisations in the Mediterranean and Middle East. By the 1880s the French empire began to encroach on the region, facing much resistance against direct control, like many African nations. Eventually in the 1890s it became part of French West Africa, and known as French Sudan. Born in 1921 in the cosmopolitan city of Bamako, Seydou Keïta received his first camera, a Kodak Brownie, from his uncle in 1935. His interest and technical skills developed, and by 1939 he was making a living as a photographer, opening his own studio in 1948. Keïta quickly became well known for his portraiture, with tourists and locals alike travelling to Bamako to be photographed by him. His photographs illustrate his ability to connect with the subject whilst still maintaining a sense of formality, with his the natural yet deliberate way of placing hands, the deliberate placing of folds in a dress, or the slight angle at which they would stand.

The distinctive style and approach to portraiture by Keïta was clearly influenced by Western/French colonial ideals of the time, however, African style permeates each picture. This affinity to their roots can be seen in the ladies’ extravagant dresses with bold print, and wonderfully quaffed hair or head wraps, or the traditional attire of the older male subjects. Most of his subjects were also given props of stylish items such as fashionable glasses (without lenses), luxury cars and vespas, gloves and hats – with the French beret and Breton T-shirts as recurring items, making the French influence unmistakably, but perhaps painfully, visible. Often illuminated by natural light, these symbols of modernity, combined with backdrops of traditional African prints, had a way of elevating anyone who stepped into his studio. Perhaps it is this contrast between the traditional/stereotypical image of Africans with the modern western fashion that captures people’s imagination today.

Keïta’s iconic portraits present an era that was in the process of being thrust into modernity, full of promise, strength and pride, with a slight hint of rebellion

In 1956 began the separation from the French community and internal autonomy of French Sudan, and by 1960 the independent Republic of Mali was formed. Keïta quickly became the official photographer of the new socialist government in 1962, and soon after closed his studio. Although Keïta retired in 1977, his archive of 10,000 images only came to light in the 1990’s thanks to André Magnin, the then curator of Jean Pigozzi’s Contemporary African Art Collection.

Through the new enlarged prints made with Keïta’s negatives, and with his direction, the world can now see a side of West Africa in the 1940s and 50s that they may not have known, challenging their perception of Africa, and breaking apart from the stereotypes and whitewashing of (colonial) history. Keïta’s manner of capturing the unique characteristics of the portrayed, from different echelons of society, granted them each a voice, and a calm independence that had not been seen before by a wider western audience. Soldiers standing proudly in crisp uniform having fought for their country and (former) colonial power, handsome young men with big collared shirts holding flowers whilst leaning nonchalantly with one foot on a stool, expressive women laying on a chaise longue looking directly at the camera. These are all images of the 1940s and 1950s that many are familiar with, and yet removed from a white context, and placed in Bamako, Mali, they make us question our preconceptions.

French and African influence on each other is still a point of tension. However these photographs show a strong and positive Africa which is contrary to the unifying blanket portrayal we encounter in the West. Post-colonial recognition and presentation of the rich cultural history of former colonies is lacking, and the (relatively) recent celebration of photographers and artists like Seydou Keïta have been a long time coming. With the rise in independent African designers choosing to embrace strong African style, and the gradual mainstreaming of recognisably African print, perhaps the influencers of fashion are also now being reversed.

As we look again into history, and inevitably our colonial past, we continue to ‘discover’ great artists and photographers that have been overlooked, as the contemporary perspective moves away from the dominant white male gaze. It is important to acknowledge the influence and effect of colonisation, whether it is through looking at fashion in portraiture in post-colonial West Africa, or research into forgotten “German” railroads in Togo. Photographers like James Barnor, Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, starting their careers with their affordable, small handheld cameras, developing their skills through the decades, are not ‘fresh’ or ’new’. As a matter of fact, it is us who are learning to see the beauty in the unfamiliar and the importance of (self-)representation; this has not only historical value, but is also set to expand our world view and shrink the divide between the Global North and South.

Seydou Keïta - Bamako Portraits is on view at Foam Fotografiemuseum until 20 June 2018.

Untitled, 1949/51, Untitled, n.d., Untitled, 1957 © Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

Seydou Keïta

Born. 1921, Bamako, Mali

Died. 2001, Paris, France

© Seydou Keïta / SKPEAC / courtesy CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva