One of South Africa’s finest and eclectic photographers, Graeme Williams, grew up in the suburbs of Cape Town in the 60s and 70s, during the cloudy days of apartheid in South Africa which saw the meteoric development of racial laws and colour neighbourhoods. Being a tremendous young man, Graeme built a strong connection with nature while spending his weekends walking along the many Table Mountain paths; most times he’d spend his holidays in the Cederberg Wilderness Area—that’s about 3 hours’ drive from Cape Town. His interest in photography began to see sunlight when he was about twelve years old. While nurturing a strong passion for the art, he took up a job at a bookstore until he could save some money and afford a decent camera for himself.

At that time, once he understood living under a system of legislated racism, in the form of apartheid, became his main photographic focus. To tell the story of a people fought against themselves, and a culture frayed at the watermark of colour hate and land grabbing. Because it was such an enormous dark cloud hanging over the South Africa at that time, it was difficult for Graeme to step aside from this subject matter. It was time to start documenting the frolic political situations, social heat waves and historical matters that has shaped what, and what not South Africa has become in such a turn of leaf. Many photographers at that time might misunderstood the spooling of the time for such a society that’s often referred as the ‘rainbow country’, although, for Graeme, the lens is a powerful tool for portraying the real, the mundane, and the spank of contemporary artistic beauty and appreciation.

After the dusts’ engulfing wings pulled in, that’s after 1994, when South Africa became a democratic country, Graeme felt some kind of chill with a sheer enthusiasm to [re-]focus, perhaps, widen his photographic horizon. He said,

“I felt able to explore other subjects and also to let go of the formal documentary framing – allowing for a more open-ended and lyrical approach.”

When I got reading his responses, I imagined how he exploded out of a cocoon that has casked him between situational documentary photography and photographic license. While traveling some African counties, usually on NGO or commercial assignments, he’d feel a sense of despair at the loss of what he called was once an ‘African Garden of Eden’. He’s referring to the time when Africa was flourishing in a pure, beautiful environment: uncontaminated waters, blooming forests, friendly climate, and home-made artistic objects. Now, cheap Asian knock-offs had replaced the natural flora and fauna of the African, as well as cultural materials.

The cultural history, sculptures and photographic objects where necessary to enmesh the traditional lifestyle of the people but, Chinese knock-offs are quickly replacing the African eccentric art culture. Graeme usually go on these trips often involving documenting fairly depressing-social situations, including the spread of malaria, poverty and war, in a way this project was a conscious effort on his part to shift all of these negative external experiences into a positive process of building an essay that had an aspect of beauty. No wonder, Objects of Reimiscence has taken him ten years to document through the lens; and quite interesting, it’s an ongoing project which has covered twelve African countries so far. There’s need to give Graeme a lot of attention and support for this visual project, especially, novel and impactful discoveries shall come at the helm of it. For a project that has been ongoing for about a decade, documenting the real climatic changes was not something that has come naturally, yet, he still had to add to his collection of the project when he’s on a new assignment. He said, “Usually, one has to travel light, so I now use digital Nikon cameras (D650). I always pack a cheap plastic tripod, as I often have to use slow shutter speeds.

When asked, if there’s a period in Africa where human activities didn’t pose a threat to nature. He said, “Sadly, that is not something that I have come across on my travels. I think when human populations were smaller and communities were able to live in harmony with nature, this was possible. I am not a fan of the rampant population explosion.” Things hasn’t changed, really, as against the popular cliché, because developments within the medical, farming and industrial sectors have resulted in an exponential demand on the limited land available.

Although, Graeme hasn’t limited his project to Malawi, Mali, Uganda, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania, The Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Swaziland, South Africa and Angola. But, recent assignments have determined where he travel; often the countries that he has visited were experiencing difficult social issues, and this in turn exerts huge pressure on the environment—culminating into harzards to the wildlife, forests, waters and humans as well.

Much of Africa’s natural beauty have been eroded by the daily quest for man to eke out a living and survive; from growing plants for food, cutting down of trees to build houses, and making spaces for industrial wastes. Undoubtedly. Once humans experience a sense of lack, we are forced to become more focused on survival and our connection with nature becomes reduced to one of utility. The photographer thinks that this is programmed into our DNA, so there isn’t much value in blaming others who find themselves faced with survival. African governments’ lack of capacity, finances and will, have contributed to the rampant demise of the environment. Our environs has suffered massively owing to our negligence, and social strife to survive the clamps of life. Graeme, finally opined that plastic kitsch and poor representation of animals and plants have replaced the previous splendor and colour of Africa.

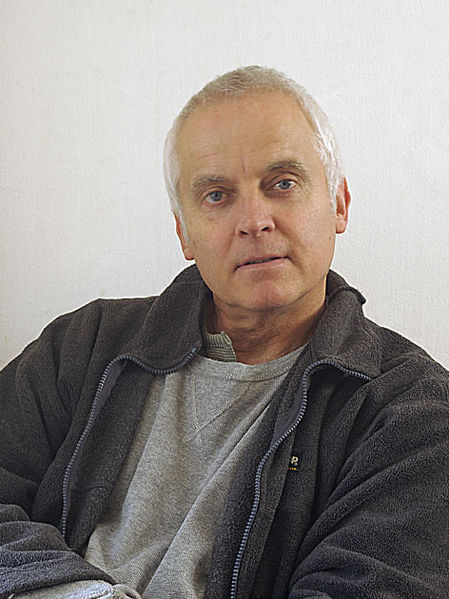

GRAEME WILLIAMS

For thirty years, Graeme Williams have worked on highly personal photographic essays reflecting his response to South Africa’s complex evolution. During the eighties he produced numerous essays documenting life under apartheid and eventually joined the collective, Afrapix. Between 1989 and 1994, he covered South Africa’s transition to democracy for Reuters and other news organizations. Since then he has concentrated on producing contemporary bodies of work that reflect this complex country.

His work is housed in the permanent collections of The Smithsonian (USA), The South African National Gallery, The Rotterdam Museum of Ethnology, Duke University (USA), The North Carolina Museum of Art, The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, The Finnish School of Photography, and Cape Town University.