‘The Machinists’ is a 2010 British documentary which follows the daily lives of workers who make clothes for popular high street brands like Primark, H&M and Zara in the garment factories of Dhaka, Bangladesh. It is the first in a series by the projection company Rainbow Collective on the subject, with ‘Tears in the Fabric’ and ‘Udita (Arise)’ following swiftly after. Avoiding sensationalist storylines directors Hannan Majid and Richard York focus on the daily lives of three women garment workers and a union boss who want the fashion industry to stop making a profit at the expense of their workers.

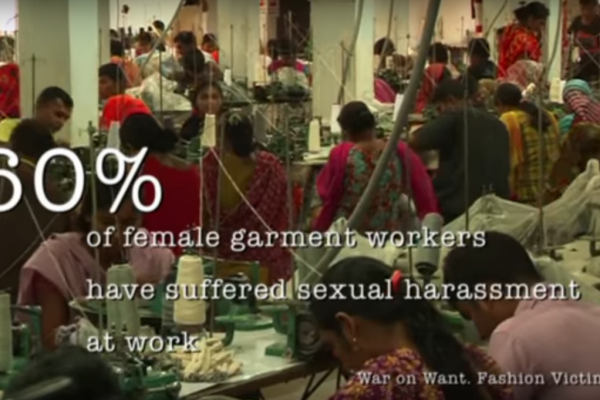

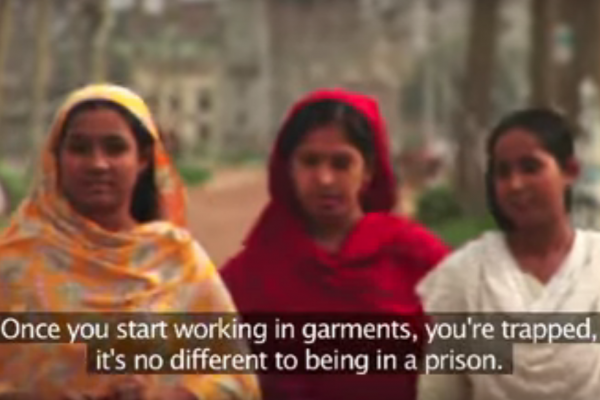

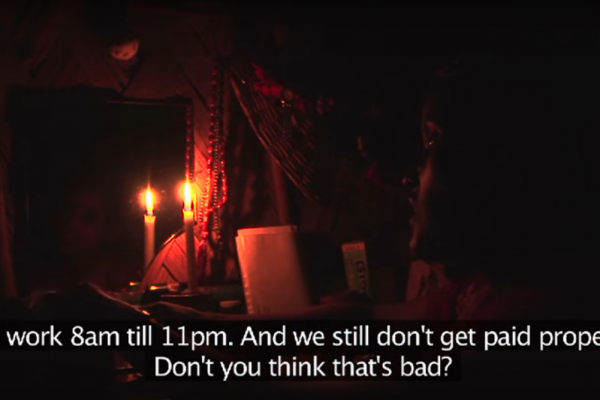

The film begins with Amirul Al Haq Amin, the president of the National Garment Workers’ Federation, explaining what the situation is like for factory workers in Bangladesh. Amin outlines that his union simply aims to achieve a fair wage, better working conditions, equal rights, dignity, and specifically wage and promotion for the women workers in the garment sector. Through showing the audience the struggles at work and at home of the three machinists, and their long hours, Majid and York then humanise these workers and allow the audience to be able to empathise with them. Nargis is a single mother who began working on the machines when she was 11 or 12 and lives in one room with seven other family members. Then there is Ratna, who started working in garments when she was 9 years old, lives alone and sends what little she can to her mother and sister who live in her home village. She is paid a wage of $45 a month, even though the monthly cost of living in Bangladesh is $64/month. Finally there is Mohammed and his wife. The couple are struggling to make ends meet, and nevertheless are determined to put their daughter through school, and provide her with the opportunity of a better life than they have, so she can look after them in their old age.

Two striking elements when watching this documentary is the pace and the continuous lack of monetary certainty in their lives. They are always in a hurry. Rushing to drop their children at grandparents, rushing to work, rushing for lunch, rushing home to spend a small amount of precious time with their loved ones, days-off perhaps once a month and frequent forced overtime. This unsettling sense of their never ending attempts to keep up with money and time is consistent throughout the film, especially considering their livelihood is at the mercy of the factory owners. The women recount the numerous ways their wages can be affected: If you are a minute or two late, you lose your day’s wage. Sometimes they were paid on the 10th of the month, or on the 20th, or even not at all. If you miss one day of work you get three days pay docked. Factory bosses would lie about missing days to makeup for loses, and if quotas or deadlines or quotas are not reached it comes out of the workers pay. And if they complain or try to organise protests the management would make threats, hire thugs to intimidate, or simply fire them.

‘All the things we make here – jeans, shirts, clothes… I wish people would buy clothes with a conscience’

This documentary highlights the effect of neoliberal capitalism which devastates the Global South and benefits corporations of the Global North. While it was supposed to provide economy to developing countries it is instead perpetuating poverty by allowing the Global North continue to be economically dependant on former colonies and not being self sufficient.

The stories of the machinists forces us to confront the reality of our cheap, ready-to-buy clothes through demystifying their origins. The rise of garment factories which push out mountains of clothing are a result of supply and demand from shoppers on western high streets. This problem is not an unknown one, as strikes, unsafe working conditions and fatal fires occasionally make headlines. We are complicit in this terrible system however when something like the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in 2013 happens, and our passive consumerism, allows it to continue. In the Global North we continue lie to ourselves, aghast that at what happens somewhere far away, believing that we are simply observing from the sidelines.

By refusing to acknowledge the impact that our choices have on someone else’s lives we are perpetuating the problem. However, by questioning, by altering our habits and by not being passive, we can change this.

What can you do?

Shop Ethically: Become aware of where you shop for your clothing, and choose sustainable brands which hold high ethical practices, such as People Tree. You can do with this online research with websites such as Project Just or Wear Well or by using apps like Good on you, Good guide, and Done Good.

Support local designers: Shop locally and choose quality clothing over cheap garments made abroad that probably won’t last the test of time.

Give old clothes new life: Avoid contributing to the supply and demand cycle that comes with purchasing new clothing by shopping in vintage and second hand stores, or repair and revamp clothes you already own.

Become Informed: Read articles, books and news from different outlets, and attend events in your city like this one in Amsterdam: True Fashion Talks: ‘How to campaign for Change’

Corporate responsibility: Demand transparency on fashion supply chains. Support organisations that advocate for union labour rights to hold brands accountable for the working conditions of their factory workers:

War on Want | Clean Clothes Campaign | Fashion Revolution | Know The Chain | Rank a Brand

“The Maquila Solidarity Network (MSN) is a labour and women’s rights organization that supports the efforts of workers in global supply chains to win improved wages and working conditions and greater respect for their rights.” They have helped in reaching landmark Accords like this.

The Trailer

The Whole Documentary

Hannan Majid & Richard York

Hannan Majid and Richard York met at film school the early 2000s in Leeds. Together they founded the film production company, Rainbow Collective, in 2006 which deals primarily tackles human rights and children’s issues.

Website

Location

Dhaka, Bangladesh