Karl’s Culture and Colours

Karl Ohiri is a British-Nigerian artist using photography, archives, and the everyday objects to tell his story, especially as a young man who grew up in a rather, racial community at that time. Personal experiences form the basis of his profession exploring themes reflective of his social life and education. The Impact Journey interviewed Karl Ohiri to dig up the experiences, works and influences to why his art focuses on the social, political, and the autobiographical. I really had a good time with Karl, and the anticipation that meddles to his work, Lagos Studio Archives showcased at the LagosPhoto Festival.

“I CHOOSE THESE THEMES BECAUSE THEY ARE VERY BROAD WITHIN THEMSELVES YET OFFER A VERY NICE TRIANGLE OF EXPLORATION THAT WILL ALWAYS REMAIN POIGNANT TO OUR UNDERSTANDING OF HUMANITY”

iMPACT JOURNEY: Where did you grow up, and how did you find living there?

I grew up in a single parent household, just the three of us, my mother, my eldest sister and me. I was raised in a small town called Eltham in the South-East of London. It’s a quiet little no frills working class town where not much happens. It gained media attention in 1993 due to the unprovoked Murder of a black teenager called Stephen Lawrence. The murder didn’t surprise me at the time as it was a tough place to live during the 80s and 90s due to the lack of ethnic minorities. My family was one of the only black families in the area so racial abuse, community bullying thrown in with a sprinkle of institutional racism were just a part of daily life for me whilst growing up. Although it was a tough place to live in due to the openly racist attitudes of large sections of the town it was a place that fascinated me. I learnt many lessons from just observing my surroundings – life lessons that have shaped my understanding of the world, for example; I learnt that most racism stems from fear, and that for every evil person there is a good person but most of all I learnt that love always wins in the end and the power of love and compassion is the greatest gift we can possess.

Q: What was your exposure to documentary photography, and who were your early influences?

I got in to documentary photography through regular visits to Nigeria. I would regularly go back from an early age and see family – I think my mother was keen to take us to Nigeria partly because of my upbringing, my mother always wanted me to know there was this place called ‘home’, a place full of beauty that I would always feel welcomed. When visiting Nigeria I would often take my camera and document scenes I found peculiar or different to my life in the UK. The camera became a tool I could use to make sense of this space. So in 2007, whilst studying photography at Goldsmiths University in London, I decided to focus my dissertation on the notion of home and produced a body of work entitled: A Place Called Home, looking at the strange and familiar and critiquing the insider/outsider relationship I become a part of every time I return. I shot the project in black and white to emulate the work of the greats I’ve admired like Henri Cartier- Bresson and Sebastiao Salgado. I loved the way they used black and white photography to capture amazing images of people and places and it was their images that really got me inspired to pick up a camera and shoot.

Q: Your documentary photographic works have been featured in national and international exhibitions, such as the Alchemy Festival, Omenka Gallery, FNB Joburg Art Fair, and others. How does it feel to showcase your works at these famous exhibitions?

It is always a lovely feeling to show at prestigious exhibitions and events. It’s a nice sense of accomplishment as you get the opportunity to exhibit side by side with artists you admire or within spaces that have an amazing history within the arts. Another benefit of such exhibitions is that they tend to get a high volume of visitors, which is great as I feel art should be seen and experienced. I get excited to think that someone may encounter one of my works or a project I have been involved with in such an exhibition and that it might inspire them. So many photo-shows I have been to have this effect on me so it’s great to think I could potentially do the same for someone.

Q: You are a successful documentary photographer, and while your individual artistic talent is clearly astute, you chose to focus on the notion of family, identity, cultural heritage and popular culture. What made you chose these themes?

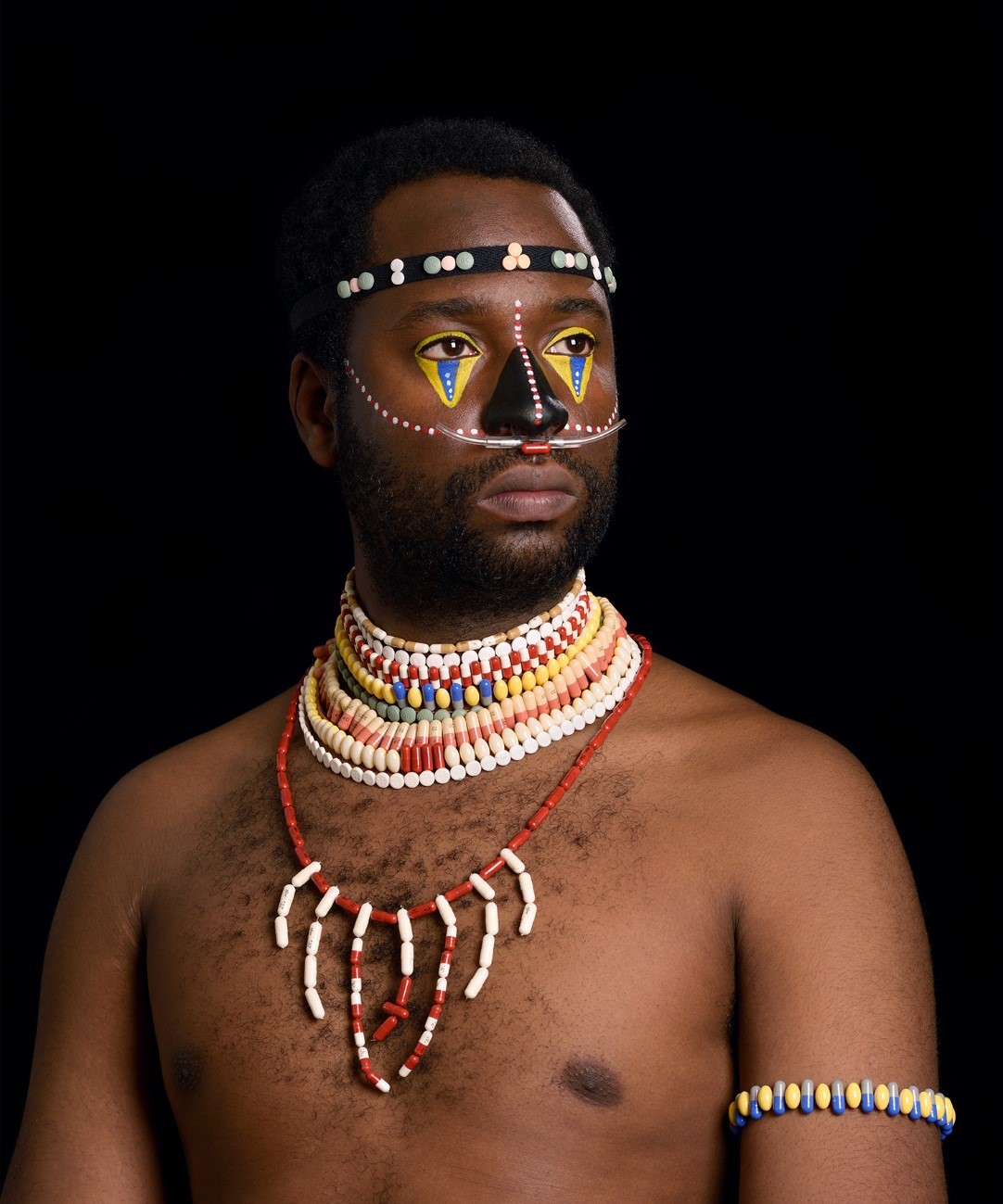

I never had the money or time to do elaborate projects where I would travel the world so out of circumstances I started to work with themes that formed part of my daily existence. In doing so it has enabled me to produce work that I have a connection with and feel strongly about. I choose these themes because they are very broad within themselves yet offer a very nice triangle of exploration that will always remain poignant to our understanding of humanity. I hope through taking this approach the works feel sincere and have elements that people can relate to. I have always used art as a tool for reconciling fears and desires, using the photographic medium has allowed me to overcome difficult periods in my life and share the process with an audience. For example, when my mother passed away suddenly in 2012 due to cancer I was in a tough place in my life. Through photography I was able to explore alternative realties and create worlds of escapism. Medicine Man is a prime example of this – using the left over medication my mother left behind after she passed away I create a fictional character that in an alternative reality could have saved her. The photographic process becomes an act of mourning and reflection and serves as a constant reminder and record of a tragedy that I bared witness to and came out stronger.

Q: How would you describe your style of photography, and has it transformed over the years? If so, what were the factors that affected the transformation?

I would describe my photographic style as hybrid as it can often feature traditional documentary images that aim to capture a decisive moment and then there are images that are staged and are more to do with conveying an emotion. I think that this is where my photography has changed over the years. Where before I was concerned with capturing things in real time, which is often very stressful and would not clearly represent what I wanted to portray. I now use photography to its full potential and often stage my images. This allows me to be more playful within the photographic medium and construct meaning through the careful placement of objects, possess and gestures I insert within the frame. Using historical references I allow the viewer to explore my intended meaning, although this will still be subject to individual memory, it provides me with more control over the desired effect of what I want the audience to take away from the image. This transitional approach has meant that I can revisit space and time and redefine the notion of the decisive moment.

Q: At the LagosPhoto Festival, and considering the 2018 theme: Time Has Gone. What kind of works did you showcased?

I showcased a curatorial project called Lagos Studio Archives. The project started in 2015 after having a conversation with a studio photographer in Owerri, Nigeria. We had a great conversation about photography that led to me asking to see some old studio portraits in his archives. His response was that he had put up his entire collection of 35mm studio photography in the dustbin a week before my arrival. When I asked him why he dumped them off, he said it was a very common thing to do, and that all of his friends in the field had done the same thing once they switched over to digital. When I went to Lagos the following year, I met up with a photographer friend who runs a studio in Lagos and asked him if he had any film negatives I could see, he told me a similar story – he’d burnt his negatives a couple of years ago as they sat in his studio, filling up space. It was after talking with him and other photographers in the local area that I realized that this was common practice for many of the old film photographers in Nigeria who had since adopted the digital medium. I decided to put a call out to photographers who were throwing away their negatives. The purpose of the project is to save some of the archives that were close to extinction that I came in contact with and to raise awareness for future generations about the importance of preserving photographic cultural history. I hope the project can shed new light on studio portraiture in Nigeria and provide a platform for critical discourse.

Q: Did your works at the LagosPhoto Festival reveal a new context from the social, political and the autobiographical?

The work I presented at LagosPhoto is a continuation of the exploration of the social, political and the autobiographical. All of these contexts are present in some form and have given rise to the project being developed. The archive is a social product that encapsulates a vast demographic of Lagos inhabitants. The politics of the time is present within the attitudes of how the sitters choose to be represented within each decade and the autobiographical plays a huge part to the project as it draws on a passion and love for Nigeria which has been installed from an early age due to regular visitation which has made me interested in my cultural heritage and feel the need to share it with others. So as far as context is concerned, I see all heading in the same direction.

Q: Would you consider any collaboration on documentary photography with iMPACT JOURNEY in the future?

I love the work that iMPACT JOURNEY are doing so if an opportunity to collaborate came up in the future, I would love to!

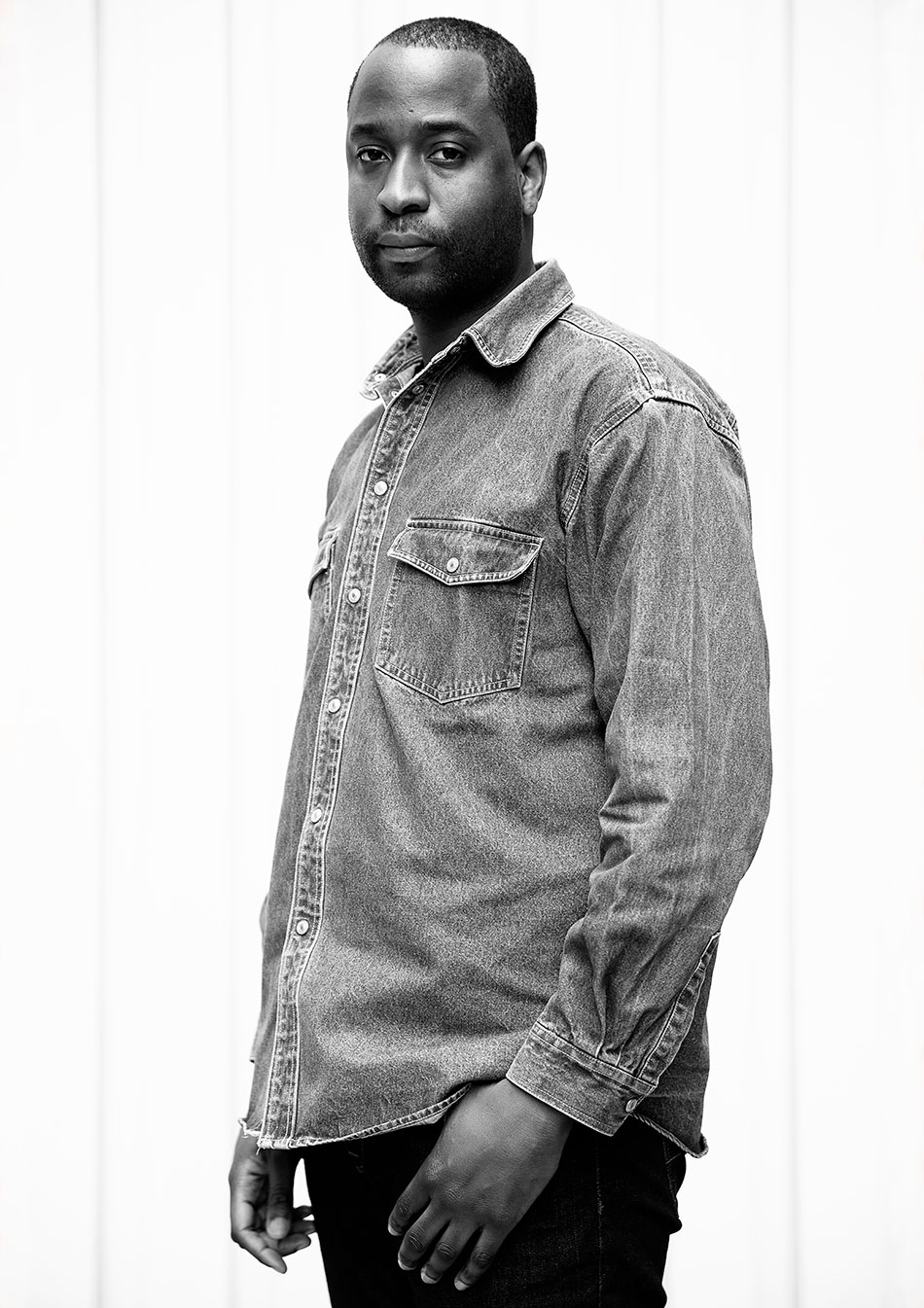

Karl Ohiri

Karl Ohiri is a British-Nigerian artist using photography, archives, and the everyday objects to tell his story, especially as a young man who grew up in a rather, racial community at that time. Personal experiences form the basis of his profession exploring themes reflective of his social life and education.

Website

Location

Lagos, Nigeria